Legal pathways in a dynamic environment

Exploring the Chinese Civil Code through comparative analysis

Private Law Gazette 2/2022 – China’s economic and political stature demands a scholarly response that can surmount linguistic as well as cultural barriers. Much is spoken nowadays of a growing need for competence on China. The Institute can look back all the while on a long scholarly tradition of covering Chinese civil law. The existence of a dedicated China desk goes back to Berlin, to what was then the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Comparative and International Private Law. Legal scholar and sinologist Knut Benjamin Pißler has been running its counterpart at the MPI since 2002. Under Pißler, what used to be the China desk has expanded into the Centre of Expertise on China and Korea. We join Pißler at his workbench for a closer look.

Pißler researches the legal framework for both private and commercial relationships among businesses and individuals in one of the world’s most dynamic settings. Currently he has taken on a project, planned to last several years, that will create a roadmap for research on the Chinese Civil Code of May 2020, which entered into force in 2021.

Basic legal research goes bilingual

A four-person team consisting of Pißler and three other current and former Institute staff members inaugurated the project by translating the entire code into German. Their translation was published in the German Journal for Chinese Law (ZChinR) in late 2020. It is annotated with paragraph headings and explanatory footnotes that reference pre-existing law and show the code’s substantive and terminological changes vis-à-vis various predecessor statutes.

“This bilingual basic legal work could only have been accomplished with the knowledge of Chinese legal culture accumulated over decades at this Institute”, says Pißler. The annotated translation has already served as a foundation for numerous conferences and meetings about Chinese civil law.

„It is interesting to see how European concepts are in some ways adopted but in other ways adapted to China’s particular needs. And China more and more is going in a completely new direction.“

– Knut Benjamin Pißler –

Conveying Chinese legal concepts

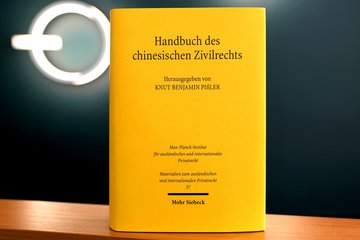

Pißler, as editor, in conjunction with a team of academics and legal practitioners, is currently preparing a handbook on a broad range of topics. Its overall purpose is to make the Chinese Civil Code accessible to a readership of German-speaking lawyers. It will also address core questions of Chinese legal concepts, for example about how rights are enforced and obligations met.

“Whereas in Germany the substantive civil law is understood to be a system of parties’ claims (Ansprüche), China’s approach can seem reminiscent of international unified law,” Pißler explains. “The differentiation between substantive and procedural law there is not entirely clear; in effect, you have a system of legal remedies based on obligations not having been met, or on a violation of rights.” The handbook explores how this approach affects the understanding of Chinese law.

A multifaceted body of commentaries

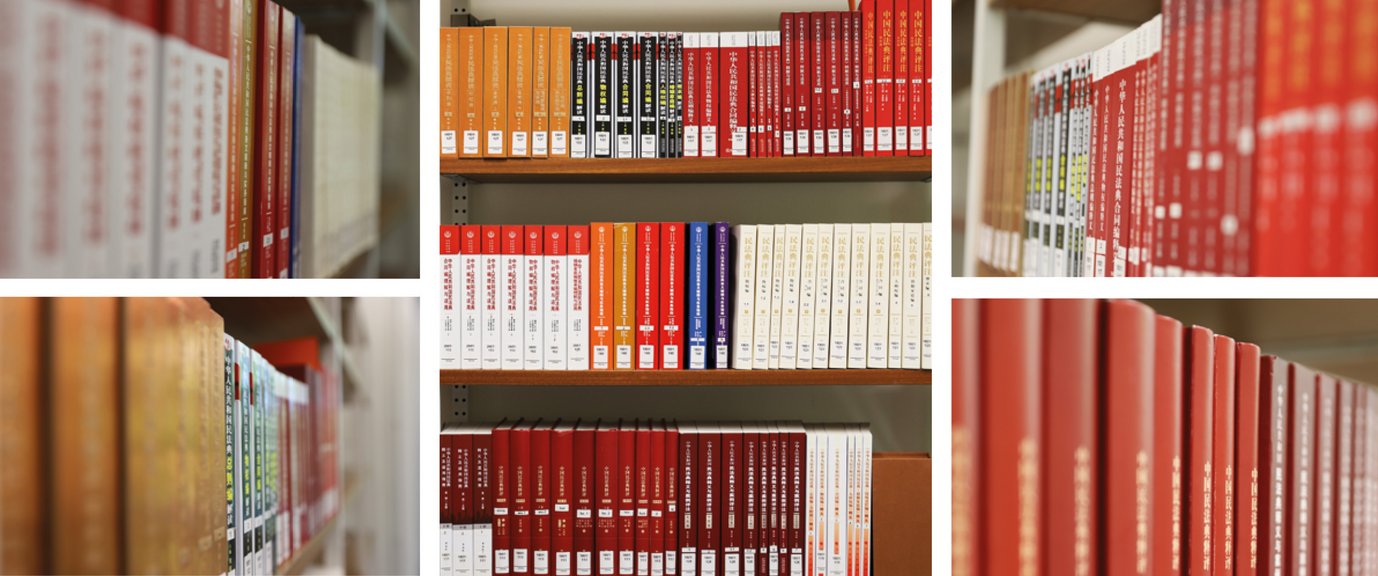

But what is the perception of the new Civil Code in China now, almost two years after it took effect? What problems have emerged in the application of the law? Pißler has begun examining and developing a preliminary analysis of Chinese commentaries on the new Civil Code. “In China, as in Germany, commentaries on laws are an indispensable everyday working tool for lawyers. They have a very old commentary tradition there that was revitalized during the reform-and-opening process of the last decade of the twentieth century”, Pißler says.

So far, he has found that the Chinese commentary landscape in terms of size and diversity has become a match for Germany’s, notwithstanding some persistent differences – for instance, of academic rigour. The Chinese publications in the collections of the Institute library alone occupy several linear metres of shelf space. The commentaries fall into three broad categories: those by authors who took part in the legislative process; a series published by the Supreme People’s Court, addressed primarily to judges; and a relatively large number of scholarly commentaries.

Comparative law as a compass for Chinese jurisprudence

The transformation from socialist to a more market-oriented economy; the growing wealth of millions of people before a backdrop of technological advancement; the tension between opening and isolating internationally: each is a major challenge for China today. Given that China is the world’s second largest economy, Chinese legal developments are highly relevant for China’s partners around the world.

Western-trained lawyers who work with Chinese law need to understand and evaluate not only the parallels with their own legal systems but also the unique features of China’s culture, society, and politics. As a matter of legal policy, does a legal transplant such as the doctrine of contracts that are void on grounds of unconscionableness serve the same purpose there? Does it have the same effect in practice? As a matter of comparative law, how do legal transplants emerge as altered compared to the doctrines that inspired them? What were the underlying considerations? In the context of rapid transformation, the development of Chinese private law will remain an exciting field of research.

“The reception of continental European civil law has been, and continues to be, a major influence in the People’s Republic. The German Civil Code is still regarded as an important influence, but it is far from the only influence”, Pißler has found. “It is also interesting to see how European concepts are in some ways adopted but in other ways adapted to China’s particular needs. And China more and more is going in a completely new direction”.

© Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law / Johanna Detering