From Generation to Generation

Transfer of property through succession, contract and religious trusts in Islamic law

Traditional notions of family, marriage, and parenthood around the world have changed significantly in recent decades. The result is often that black-letter law is at odds with both actual practices and the social reality. Since 2009, the research group “Changes in God’s Law” at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law has been studying developments in the civil law of Muslim jurisdictions. The group is led by Nadjma Yassari. One of its current focuses is the law of succession.

How is wealth transferred to the next generation? How much freedom do testators have in naming heirs by last will? What is the role of the state? What types of family arrangements does the law privilege and what types are undergoing shifts? A multi-year research project is underway to find answers to these and other questions. A glance at a map of the Muslim world makes it clear how complex a task it is: Is Islamic law a monolith, or are there a number of different Islamic legal systems? The answer is still being debated. What is certain is that “the law of God” defines a framework within which each country arrives at its own solutions.

Great diversity under a common tradition

Iran’s law of succession, for example, is codified comprehensively whereas Saudi Arabia has not codified its law of succession in any way, distributing estates instead according to rules drawn from interpretations made by Islamic scholars. Other countries such as Iraq have enacted statutory frameworks for some aspects of succession law but not for others. Where does this diversity come from?

“Each branch of Islam has developed its own law of succession, and there are differences even within these branches. The concepts and the terminologies Islamic legal scholars work with is something they all have in common,” Nadjma Yassari explains. “By interpreting the source texts, they are united in the Islamic legal tradition.”

Differences from the European legal tradition

The Islamic law of succession is fundamentally different in several respects from the European regimes that developed in the Roman legal tradition. Gender parity and the scope of a person’s freedom of testation are two salient examples. The power to regulate the transfer of one’s estate through a last will is starkly limited under Islamic law. The legal heirs of the deceased inherit fixed fractions of the estate by operation of law; testators can freely bequeath only one third of their estates. Some scholars even impose limits on the circle of persons who are eligible to be named as legatees in a will.

“Broadly speaking, men and women receive unequal shares of the inheritance,” says Dominik Krell, a research assistant with the group. “Our research right now is basically about learning what that looks like in practice.”

He gives two examples of phenomena from different jurisdictions: Iranian parents can take advantage of a special contractual arrangement in order to transfer their assets inter vivos to their sons and daughters equally. In Saudi Arabia on the other hand, one can observe how some segments of the society desire to keep the wealth within the agnatic line. This is done by setting up trusts the beneficiaries of which can only be male descendants.

Interdisciplinary basic research

One of the project’s central aims is to shed light on the economic and social functions of the law of succession. “Calculating shares of an estate is not the main thing we are working on,” says Nadjma Yassari, describing the project’s substantive work. “Instead we’re looking at the societal context in which wealth is transferred between generations.” This kind of basic research requires subject matter expertise above and beyond the purely legal. As one of the world’s few interdisciplinary teams grappling with the current laws of Muslim jurisdictions, the research group, in which sociologists, political scientists, and scholars of Islamic studies are as involved as the legal scholars, meets the criterion.

Long term prospects

Since the research group’s overarching ambition is to generate a long-term academic accounting of the reforms and transformational processes underway in Muslim jurisdictions, the work of the succession law project is slated continue for several years. “Basic research in the legal field is concerned with the breadth and depth of society’s major legal questions,” says Nadjma Yassari. “The goal is to prepare; when a case raises complex issues that acutely need an answer, we can be ready to provide one.”

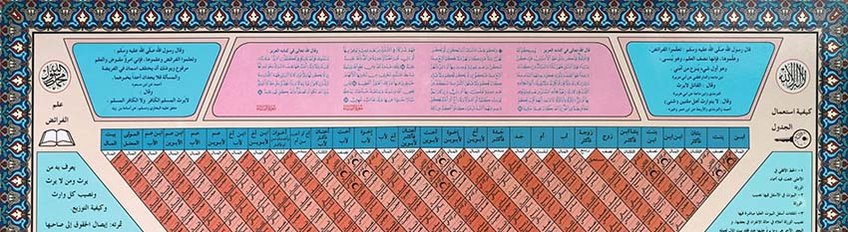

Header image: Table of inheritance rights according to Hanafi law.

© Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law / Johanna Detering