Scholarship in Pictures and Stories

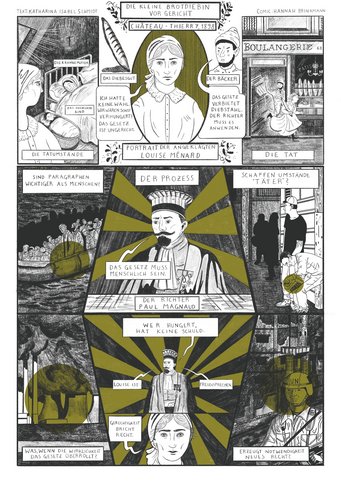

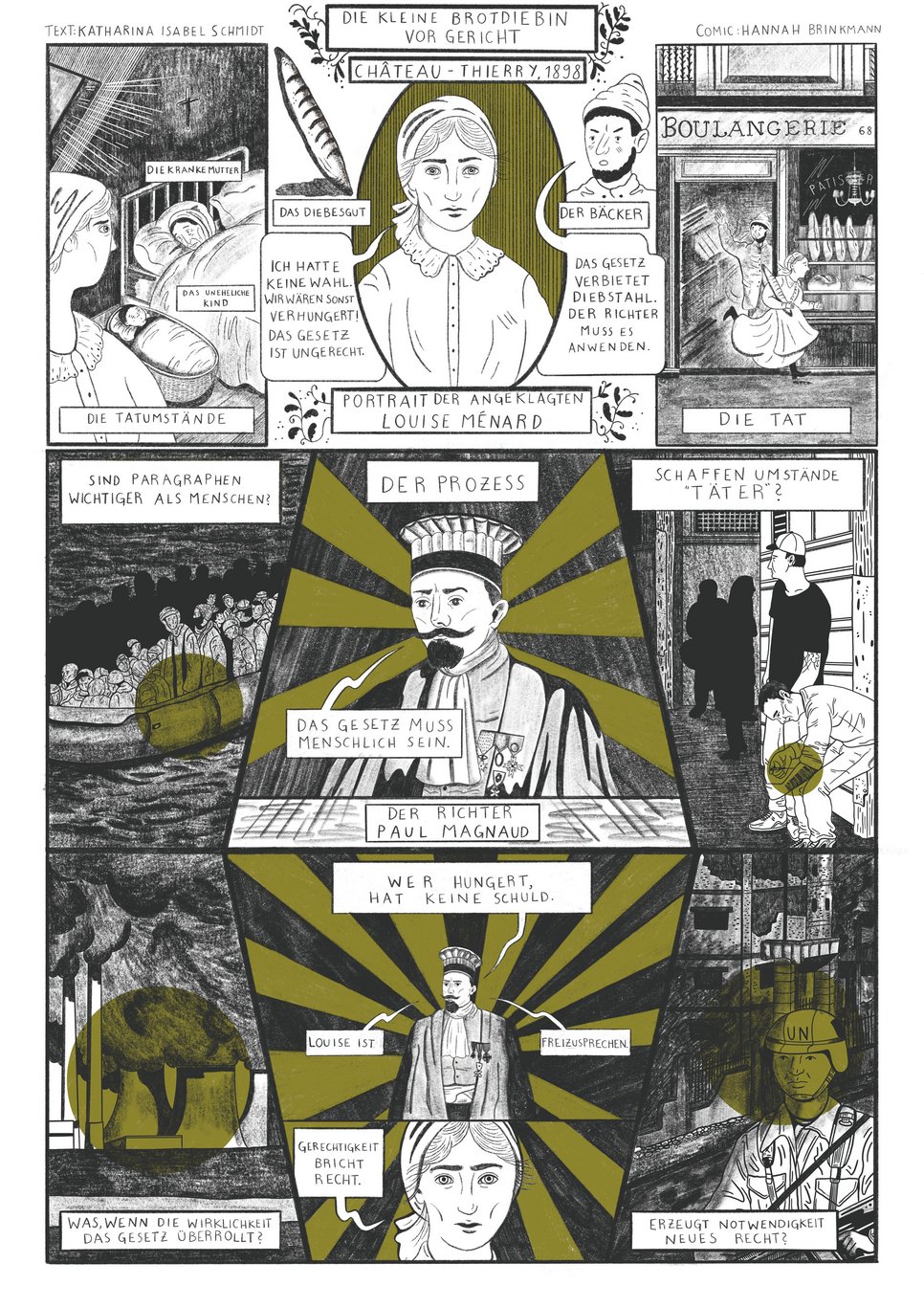

The Young Academy Fellows of the Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Hamburg have for a number of years been using science comics to present their topics of research. Katharina Isabel Schmidt, Research Fellow at the Institute and Young Academy Fellow, has authored a comic together with artist Hannah Brinkmann. With a handful of words and powerful images, they tell the story of a historical court case in France that remains thought-provoking today. “The little bread thief on trial” illustrates the conflict between written law and lived justice, a conflict which is at the heart of modern legal philosophy.

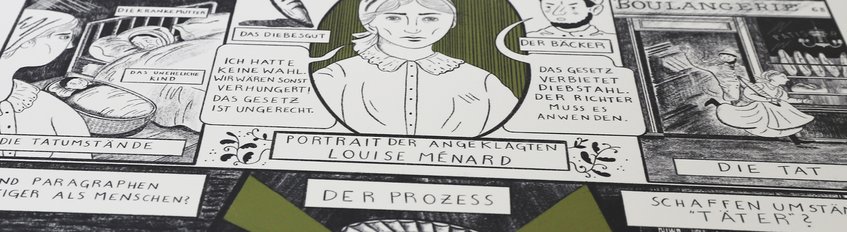

In 1898 in a French village, the young mother Louise Ménard took a loaf of bread from a bakery without paying. The suffering woman had not eaten for two days. Paul Magnaud, already known in his day as a “good judge”, acquitted her of the charge of theft. His reasoning: Those who are hungry cannot be blamed for their actions. The letter of the law must be secondary to the spirit of justice in this case.

Hannah Brinkmann has often dealt with political issues in her artistic work. “Especially with legal issues, the protagonists are important for our understanding of a problem. I immediately found the incident and its relation to today’s world intriguing,” said Brinkmann in describing her engagement with the young mother's case. One particular challenge was to tell a story in just a few pictures. She found a model for her creative transposition in a 19th century visual format known as broadsides – namely, street posters which reported on criminal cases with highly emotive words and pictures.

‘As a legal historian, I also tell stories about the law,’ says Katharina Schmidt. She has previously analysed the trial involving the ‘little bread thief’ in an academic article. “It's an enormously important case for the philosophy of law. The story makes it possible to grasp a highly abstract conflict. The acquittal by the ‘good judge’ raises the question to what extent the written law can take proper account of the reality of life and the beliefs held by individuals.”

How did Hannah Brinkmann approach the subject? “A courtroom is an exciting setting. Things are addressed in a closed chamber that can have a profound impact on our lives – in both a positive and negative sense. A drawing makes it possible to weave these two levels – the emotional level and the personal consequences – into the representation of the trial.”

“Science comics are particularly well suited to telling stories about supposedly minor figures and their contribution to legal history and reforms. The fact that ordinary people are behind such developments is often overlooked,” says Katharina Schmidt. “The issue of legal certainty was a huge topic at the end of the 19th century. It was the era in which the major codifications of law emerged in Europe, and there was a fear that the law might lag behind developments in modern life. The case of the little bread thief was picked up by the press not only in France, but also in Germany and the USA. Some commentators even went so far as to cast the case as an instance of legal or judicial “anarchy.” This polarisation extended into the general public."

“Science comics are particularly well suited to telling stories

about supposedly minor figures and their contribution to

legal history and reforms. The fact that ordinary people are

behind such developments is often overlooked.”

– Katharina Isabel Schmidt –

What did the collaboration between art and legal scholarship look like? “I started by designing a storyboard. It was important that Louise Ménard be introduced as a person so that readers could put themselves in her shoes in the subsequent court hearing and understand what she did. We also wanted to work out the trial setting and draw parallels to the present,” says the artist. ‘I was looking for examples that would illustrate where problems are evident today,’ adds the legal scholar. "And these are topics such as the opioid crisis and migration. We wanted to depict situations that crystallize a question without providing an answer. The aim is to encourage viewers to articulate their own thoughts.”

What is the difference between a scientific infographic and a science comic? “Infographics convey knowledge, they don't necessarily aim to reach someone on an emotional level. A comic, on the other hand, tells a story. Stories engage people, generate empathy, and cast a spotlight on unanswered questions. Together with narrative drawings, comics open up many possibilities, especially in academic contexts,” explains Hannah Brinkmann.

For Katharina Schmidt, the project has been a source of inspiration for her own work. “Lawyers tend to make demands: ‘Tell me clearly what I'm supposed to be seeing here’. But the combination of text and images leaves room for interpretation. I liked the process that we used to proceed from abstract ideas to concrete images. Naturally, I also employ verbal imagery when writing academic texts. But after this experience, I’ve tried to become even more visual in my thinking and writing about legal philosophy. It would be great to be able to write in such a way that one could easily draw the concepts and ideas in question.”

Further reading

Portrait Katharina Isabel Schmidt: © Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law / Johanna Detering