A Springboard for the Circular Economy

Private international law supporting a sustainability transformation of the fashion industry

Antonia Sommerfeld, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute, and Verónica Ruiz Abou-Nigm, Professor at Edinburgh Law School, University of Edinburgh, are investigating the legal framework for sustainable solutions in the fashion industry. Toward this end, they are focusing on circular business models which allow sustainability and economic efficiency to merge together within a circular economy. What is the role of private international law (PIL) in this transformation process? How can PIL help to ensure that sustainable business practices prevail in global supply chains?

The resources of the Earth are finite. Nevertheless, we are using them excessively. This is alarmingly illustrated by the Earth Overshoot Day. Calculated annually by the Global Footprint Network, it marks the day when humanity’s demand for resources in a given year exceeds what the Earth can regenerate in that year. In 2024, this date was reached already on 1 August. In terms of our fight for sustainability, the economic model of a circular economy is taking on a pioneering role. It aims to maximize the life cycle of products while minimizing resource consumption. Thus, it is an economic model that strives to keep goods and materials within the economic production cycle by means of repair, reuse, recycling, and upcycling; simultaneously, rather than disposing of expended resources as waste, it looks to reuse them as secondary raw materials in the manufacturing of new products. The circular model contrasts with a conventional linear economic system in which finite resources are extracted from nature for the purpose of manufacturing products that are frequently not used for their full lifespan and potential and that are ultimately thrown away.

„Circular business models are based on

contracts and property, core private law institutions

that shape our economy.“

– Antonia Sommerfeld –

Global Supply Chains

The value chains encountered in today’s fashion industry are made up of complex supply chains characterized by a multiplicity of actors, a high use of subcontracting, and various forms of precarious working conditions, all spread across multiple continents. All steps of the process, from sourcing and distribution to disposal, are globally organized. “Many of the current practices of the global fashion industry result in an excessive consumption of natural resources and an enormous amount of waste during the production, transportation, and disposal processes. The number of industry stakeholders in the field which are calling for change are increasing,” says Antonia Sommerfeld. Together with Institute Director Ralf Michaels and Verónica Ruiz Abou-Nigm, Chair of Private International Law at the University of Edinburgh, she is conducting research on the legal framework that is necessary for the realization of a circular economy.

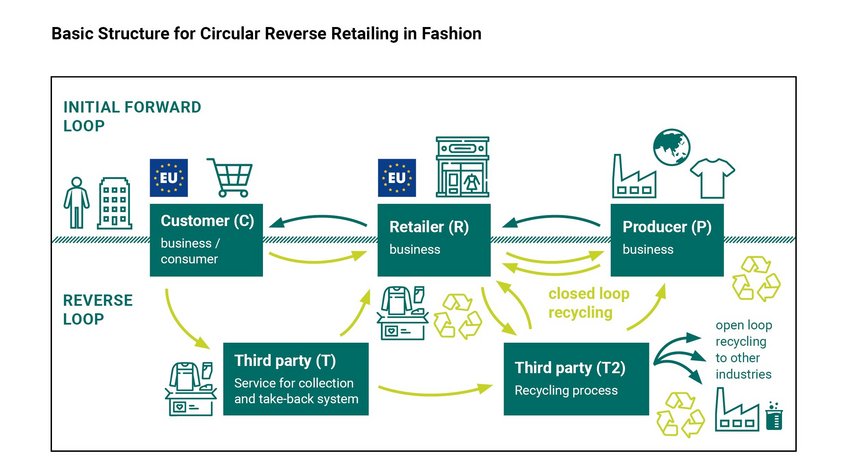

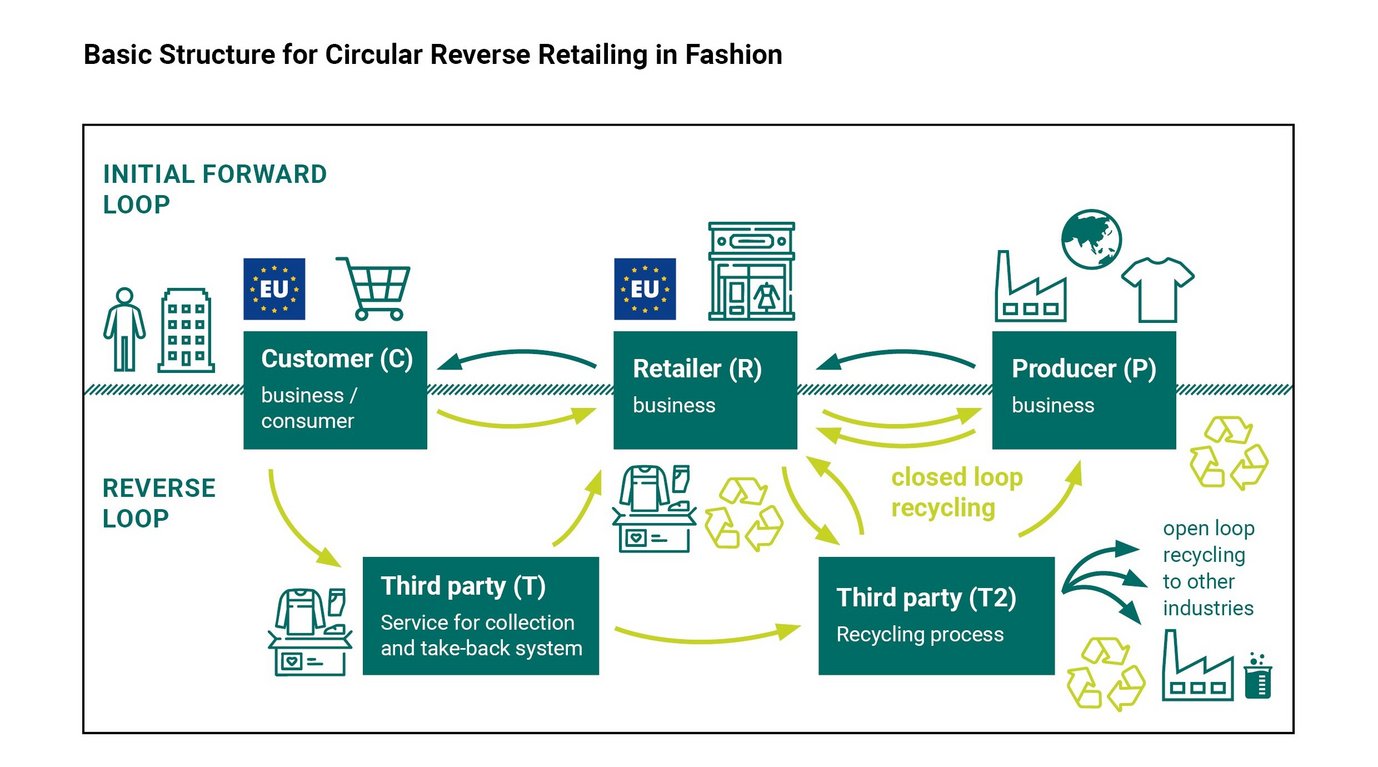

In conducting their inquiry, Ruiz Abou-Nigm and Sommerfeld first took a closer look at the circular business models currently practiced in the fashion industry in order to identify how they can be best structured legally. “Our research has shown that the most effective approach for achieving a closed loop system is circular reverse retailing. This process involves collecting pre- and post-consumer textiles and then sorting and returning them to retailers, manufacturers, or third parties for upcycling or recycling so that these materials remain in the loop and can be reused,” explains Ruiz Abou-Nigm. “Such an approach generates a number of legal issues. These include contractual obligations and liability as well as issues related to intellectual property rights. The degree of legal complexity is further increased by the internationality of the supply chain.”

Fig. 1: The varied and complex legal structures that the circular model and its reverse loop mechanisms add to the traditional linear model of a sales contract has been depicted by Sommerfeld and Ruiz Abou-Nigm in this diagram. The model of Circular Reverse Retailing is a closed system: customers return used clothing to retailers, producers, or third parties through the use of a low-threshold take-back system. Secondary raw materials or new goods achieved through upcycling and recycling are then utilized in the regular production process or are offered for sale. Additionally, materials generated in these processes that are no longer usable in the original industry, can be recycled and utilized by other industry sectors.

The interaction of rules from different legal systems

PIL determines which law applies in cases having an international dimension. Each country has its own PIL regime, and there are also numerous prevailing international agreements and European regulations which unify the PIL-rules in certain areas of law. PIL determines which country’s law will govern an international contract, which court or arbitration tribunal has jurisdiction to rule upon a case, and how a decision can be enforced in an international context. “Circular business models,” Sommerfeld observes, “are based on contracts and property, core private law institutions that shape our economy. Remarkably, though private law and private international law are crucial for a transition toward a circular economy, legal research in these fields is almost entirely lacking.”

„Our research has shown that the most effective

approach for achieving a closed loop system

is circular reverse retailing.“

– Verónica Ruiz Abou-Nigm –

Circular rethinking

The two legal scholars have analysed how the current PIL system could support potential circular regulatory approaches: “Up to now, there is no level playing field between linear and circular business models. Our analysis shows how PIL and private law instruments could help to establish a legal framework allowing a circularity transformation. We have identified the problems which stem from the currently dominant linear understanding of private law and PIL. We employ these findings to outline how, through circular rethinking, they could be overcome.” According to the researchers, the comparison between the linear and circular understanding of the relevant legal provisions reveals how through circular rethinking existing challenges can be overcome, how loopholes can be eliminated, and how laws on circular sustainability can be effectively enforced. Circular rethinking is able to foster a transition to a circular economy in the fashion industry under existing law, already. Further improvements could be achieved with additional legislative measures.

“In legal policy solutions, sustainability and economic efficiency are still predominantly presented as being contradictory. They are portrayed as if one can be achieved only at the expense of the other,“ says Sommerfeld. “Yet in terms of economic growth and value creation, recent studies identify enormous potential in circular economy systems. Individual regulations, such as the new EU Circular Economy Action Plan adopted in 2020, build on this potential. Legislation should take even bolder steps to overcome the persistence in the linear economy. National and European regulations could even create trickle-down effects in the other legal systems along the supply chains through the mechanisms of European PIL.”

„Our analysis shows how PIL and private law

instruments could help to establish a legal framework

allowing a circularity transformation.“

– Antonia Sommerfeld and Verónica Ruiz Abou-Nigm –

PIL mechanisms produce their effects in global supply chains regardless of the industry sector. It is therefore hoped that Ruiz Abou-Nigm and Sommerfeld's research will trigger further academic work. The topic has, moreover, assumed even broader significance in recent times. A key advantage of a circular economy is also the increased resilience of supply chains, a benefit which should not be underestimated in times of global and geopolitical crisis.

This research is part of a larger legal project on the circular economy that, in addition to considering private international law aspects, is also investigating the implementation of a circular economy into national private law irrespective of the industry sector. The aim is to map a path to a “circular private law” that reflects such a circular transformation in private law. The inquiry will examine, for example, how the right to repair recently introduced in the EU can be implemented in Germany, how product-as-a-service contracts can be designed for consumers, and how circular sales contracts, as a special form of sales contract, can legally be reflected. Such circular contracts are already practiced by the industry in pioneering projects. In addition, possibilities will be presented as to how private law can be supplemented with modified warranty rights for refurbished products as an intermediate category between new and used products.

For their article Circular Fashion and Legal Design: Weaving Circular Economy Threads into International Contracts, Verónica Ruiz Abou-Nigm and Antonia Sommerfeld received the 2024 José María Cervelló Business Law Prize, jointly awarded by IE Law School (Madrid) and the international law firm ONTIER.

Images:

Header graphic: © Elements from AdobeStock / YEVHENIIA

Portrait Antonia Sommerfeld: © privat

Portrait Verónica Ruiz Abou-Nigm: © Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht / Johanna Detering

Fig. 1: © Antonia Sommerfeld, Verónica Ruiz Abou-Nigm