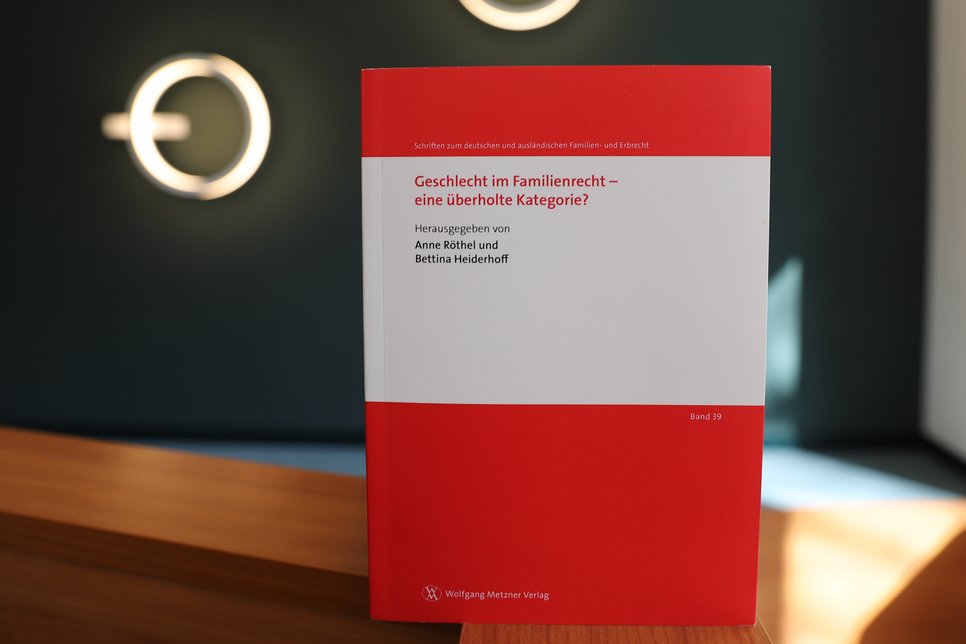

Are sex and gender distinctions in family law obsolete?

Institute director Anne Röthel has co-edited a volume in which five legal scholars explore the current significance of sex and gender in family law. Many individual family law norms are formulated neutrally as to sex and gender, using terms like “spouses” and “parents” instead of “wife” or “husband”, while others, especially that deal with descent or filiation, maintain the distinction between mother and father. The collected works examine whether these remnants of sex and gender still have a legitimate function in modern family law.

The edited volume reflects the proceedings of the sixth Fachgespräch Familienrecht discussions on family law, held at the University of Münster in 2023 under the leadership of Bettina Heiderhoff and Institute director Anne Röthel.

Anne Röthel’s contribution as author addresses the significance of biology as a basis for family law norms. Revisiting earlier family law scholarship, she demonstrates that much that once seemed “natural” – and hence durable, universal, and unquestionable – turns out to be malleable and relative in retrospect. Through multiple case studies, she examines how family law has shifted since 1900, when norms of the newly enacted Civil Code were underpinned by biological traits that also served the rhetorical purpose of epitomizing the existing civil order. She then traces a lengthy and highly contested process by which the preferential rights, privileges, and coercive powers provided in the Civil Code of 1900 were gradually set aside under the German constitution, which supplanted the earlier “natural” regime with a new legal order. In analysing the shifting treatment of trans identities, she describes the role of the Federal Constitutional Court in reviewing the reasonability of statutes whose legislative purpose derived from scientifically obsolete notions of the biological, anatomical and physiological elements of human nature.

Röthel concludes that going forward, a jurisdiction can either maintain its categorical use of sex and gender or shed gendered categories altogether in favour of a post-categorical family law. Either approach is conceivable. The allure of a post-categorical family law is that a jurisdiction going that route does not continue to lend legitimacy to family law norms that the twentieth century has already showed are unworkable. But at the same time, it has become apparent that sex and gender is less of an issue as a legal category today, now that gender itself is in some ways an elective trait. Röthel finishes by outlining topics for further research in family law: the need for a thorough and unbiased inventory of remaining sex and gender distinctions; an accounting of the concerns that the community may still plausibly regard as legitimate that can only be addressed through sex and gender-specific norms; an exploration of the ways in which post-categorial family law might be configured.

Image: © Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law