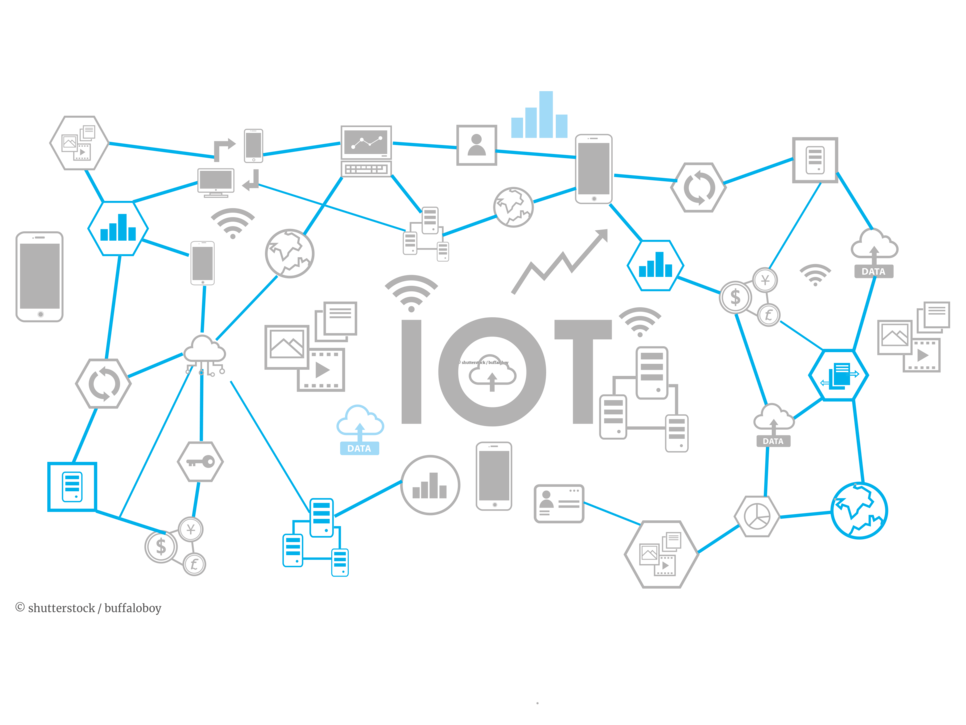

Connected devices and digital possession

Is the Internet of Things undermining property rights?

Private Law Gazette 1/2022 - Connected devices are fast becoming fixtures in our daily lives. Not only smart speakers, alarm systems and other smart home applications but also connected vehicles and health-and-fitness trackers are examples of the Internet of Things. Collectively they are among the leading twenty-first century technologies. In his habilitation monograph, Konrad Duden, senior research fellow at the Institute, examines the extent to which a connected device’s digital use is protected by virtue of that user’s owning or possessing the device.

The Internet of Things has unlocked new potential applications and created business opportunities. The interconnectedness gives providers the means to exercise permanent influence: They can lock devices by blocking firmware or cutting off access to the cloud. “You arrive at a place where control of the physical thing diverges from control of its functionality. A provider can, de facto, turn a high-tech end-user device into electronics waste”, says Duden, whose research sheds light on various facets of a potential weakening of property rights associated with the use of electronics in connected environments. “The potential for monitoring and shutting down that go hand in hand with connected use is not limited to consumer products. They’re a ubiquitous part of Industry 4.0”.

The American agricultural equipment manufacturer John Deere attracted attention recently when farmers sued over their no longer being able to maintain and repair the company’s electronically controlled tractors themselves, nor have them serviced by an independent mechanic. Spare parts required activation, and this was controlled exclusively by authorized technicians. Diagnostics and repairs relied on software available only at the dealer’s garage.

Protecting functionality

Smart-home applications like door locks, lighting, and refrigerators provided with subscription software that can be turned off unilaterally and at any time; features of cars, like heated seats and parking assistants, to be booked separately and for an additional fee; in terms of sellers and manufacturers controlling the use of digital end-user devices, the more everything goes digital, the broader the spectrum. How does private law today protect the use of these devices?

The law of contracts can provide some relief. But what if there is no privity of contract with the seller because the user acquired the device from the original purchaser? This brings us to the question of whether ownership and possession protect users seeking to utilize the devices’ digital functions. “Ultimately the question here is, what is the significance of property law in an increasingly digital world?”, says Duden.

Blocked software versus blocked connectivity

When it comes to protecting against blocking the use of a device, there is a fundamental distinction between interfering with software-based versus network-based utilization of a device. Two constellations are conceivable: one, a provider can shut down use of the device on a network, let us say, by refusing to permit the device to access a cloud server. Here, the cause of the inoperability lies outside of the device, which casts these cases outside the protections of property law. In the second constellation, a provider can lock software that is integrated in the device so that the device itself no longer works. If the integrated software is understood as a physical feature of the device, then the protections of property law will apply.

Thus the protections of property law depend on whether the prevented use is software-based and largely protected or network-based and largely outside the protected sphere. “This is unsatisfying as a matter of legal policy”, concludes Duden. “In the end, whether the digital infrastructure needed to run a device is built into the device itself or runs off a cloud server is almost completely up to the provider. So the provider itself can ultimately decide what protections users of the device will enjoy under property law”.

Better protection for network-based applications

In his treatment of the topic, Duden reaches the sobering finding that current legal protections for users of electronic devices in network-based environments are inadequate. And he has come up with some initial suggestions for how to prevent providers from hollowing out property law protections through their product designs. The first option would be to pass legislation to regulate cloud servers in a fashion similar to how the electricity and telecom grids are regulated. Moreover, general private law can provide tools that could be used to guarantee that not only those who stand in privity of contract with the provider but also the users of the device can pursue claims against the provider. This would not completely prevent the consequences of a weakening of property right protections, but it would at least cushion the impact.

Priv.-Doz. Dr. Konrad Duden, LL.M. (Cambridge) has been a researcher at the Institute since 2012. He completed his doctoral studies at the University of Heidelberg in 2015 with a dissertation entitled Leihmutterschaft im Internationalen Privat- und Verfahrensrecht (Surrogate motherhood in private international law and international civil procedure). His work was awarded the Max Planck Society’s Otto Hahn Medal as well as the German Society of International Law’s Gerhard Kegel Prize. He is a member of the “future faculty” program of the project Recht im Kontext (Law in context) at the Humboldt University of Berlin. He habilitated through the University Hamburg in 2021.

Graphic: © shutterstock / buffaloboy

Portrait Konrad Duden: © Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law / Johanna Detering