Piecing Together a Scholarly Puzzle

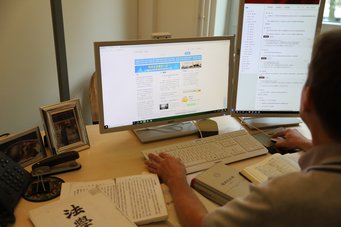

Private Law Gazette 1/2020 – At the end of May 2020, the new Chinese Civil Code was enacted. Since that time, a team of current and former Institute staff members has been working on a German translation. What in particular must be taken into account when translating legal rules written in Chinese characters into the German language?

“The current project is analogous to the piecing together of a giant jigsaw puzzle”, observed Knut Benjamin Pißler, head the of the Institute’s Centre of Expertise on China and Korea. Previously, the substance of Chinese civil law was to be found in a series of individual statutes. Now these Acts and provisions have, with some modifications and additions, been assembled into a comprehensive civil law codification.

Valuable Foundations

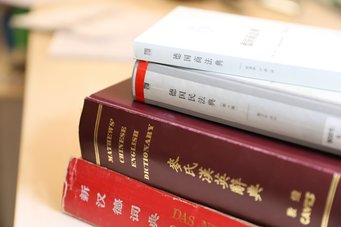

German-language versions of the individual Acts adopted in the People's Republic since the 1980s already exist. Among other resources, reference can be made to the work of Frank Münzel, the recently deceased former head of the China Unit at the Institute. In order to ensure that a linguistically unambiguous picture develops out of the previously existing puzzle pieces, the focus lies not only on compiling all of the relevant laws, but on also creating consistent terminology.

“Civil law had originally been codified in Republic of China in the 1920s. This law is still applicable in Taiwan. Our recent study has found indications that the new codification of the People’s Republic of China has resuscitated innovative concepts from the time of the Republic”, reports Pißler. It was actually Karl Bunger, the first China reporter at our predecessor Institute in Berlin, who in 1934 translated into German the Civil Code of the Republic of China”.

Fine-tuned Linguistics

How does one proceed if there is no parallel legal expression in German for a Chinese term? “The method of functional comparative law helps in the translation of Chinese terms into German, even if, based on their dictionary meaning, you are initially led to believe that there is no equivalent in German law,” explains Pißler. “We look at the context in which the Chinese term in question is used to see what function the designated rule of law has. Then we consider where the legal institution fulfilling this function is regulated in German law. The question arises, for example, how to translate – in a non-misleading manner – a term that from a German perspective has a property law connotation but from a Chinese perspective is used also in the law of obligations."

Additionally, according to the legal scholar and sinologist Pißler, it is helpful that the Chinese characters are also used for legal terminology in Korea and Japan. "We can also orientate ourselves on the solutions that have been found when translating Korean and Japanese legal terms and legal institutions into German."

Essential Prior Knowledge

A substantial familiarity of Chinese legal culture and an in-depth understanding of Chinese legal thought are of fundamental importance for the translation. The formulation of a translation that clearly ascertains the similarities and differences with German law is possible only on the basis of the expertise that has accumulated over multiple decades at the Institute in Hamburg. According to Pißler, it is always a challenge to strike the proper balance allowing German-speaking readers to identify ideas and aspects familiar from their own legal system without impeding their view of the unique cultural, social and political aspects of Chinese civil law